Preventing biofouling with bubbles

Biofouling, or the accumulation of marine life on submerged surfaces, is a significant problem for the navy and shipping industries, increasing drag and fuel expenditure. One environmentally friendly method proposed for preventing biofouling is the continuous injection of a curtain of bubbles along the bottom of the ship, allowing buoyancy to push bubbles up the surface.

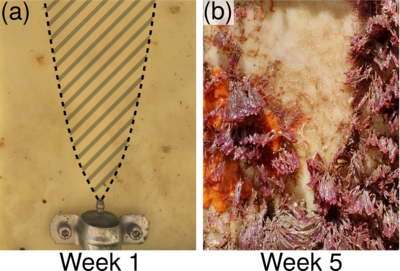

Our team has tested the efficacy of bubbling on preventing biofouling on panels submerged underwater, resulting in V-shaped clean patterns above the nozzle (top images). To learn what sets the shape of this V region, we examined the dependence of bubble trajectories (top videos) on nozzle size, flow rate, and angle in laboratory experiments. I created a video on this work for the Gallery of Fluid Motion at APS DFD that can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wouuIjoPvv0. This knowledge could inform future designs of bubble rigs, suggesting optimal spacings and required flow rates.

Computationally, I performed simulations of individual bubbles rising against an inclined wall (bottom videos) to learn how the shear stress on the wall depends on the bubble size, wall angle, and frequency of release. The shear stress can be compared to critical stresses required to remove various types of biofouling.

Adapted from

Adapted from